This is the first half of a chapter from my book “The Last Great Adventure, Part One”, (a work in progress). The second half will follow in the next few days.

In 1998 I was in Caracas, Venezuela, a partner in a gold and diamond venture with a group of South African investors. I had lived in Venezuela from December, 1993 through to the middle of 1995 and it was familiar territory to me. In the run up to the December, 1998 presidential elections my lawyer was dismayed by the polls which were indicating Hugo Chavez would probably win, and if so, he forecasted a potential coup d’etat with bloody street battles. This was the Chavez legacy in 1992 when he attempted to take control of the government and was tossed into prison. The lawyer was advising all of his foreign clients to leave the country for a month or so until well after the elections.

But where to go? I had always wanted to climb Mt. Roraima, a high mesa shared by Brazil, Venezuela and Guyana, which is home to many endemic species of plant and amphibian and was the model for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Lost World”. After a two day trek to the toe of the mountain and a one day ascent I managed to reach the top where I camped out for a few days, admiring the intricate rock formations (the Labyrinths are a must see) and the other-worldly plant life.

Mount Roraima was a fun interlude, but I was stymied as to where to go next. A friend suggested Quito, Ecuador. He had just been there at a Spanish language school and highly recommended it. Plus he said Quito was going through a hyperinflation and in US dollar terms it was very cheap. So I went back to the International Airport in La Guaira and boarded a flight to Quito. In Quito I was met by a packed minibus with a virtual United Nations of new students, all collected from the airport that day. At a short orientation meeting at the school I was told that we would each be placed with an Ecuadorian family as lodgers for the duration of our stay. Our hosts had been given strict instructions that we be in total Spanish immersion and not to respond to questions in English or other languages. That evening I was introduced to Doctor Octavio Latorre Tapia, his wife Charito (Rosita), and their sons Jose-Luis and Carlos. Thus began a friendship that has lasted now almost 18 years!

At the time, Octavio was a Professor of History at the International University in Quito. Octavio is a polymath, and can converse eruditely on almost any topic, but his passion is history. We agreed together to bend the rules “just a little”. Octavio had done his PhD at Boston College and said he was losing his English. So we compromised with the Spanish School; at 8 o’clock precisely, two quart bottles of beer would appear on the table and we would from then on only converse in English. Those two bottles never seem to have lasted too long, and on more than one occasion young Carlos was sent down the street to buy some “supplies”.

Our conversations ranged far and wide – politics, economics, ancient history, philosophy, and our respective travels. As a youth, Octavio had sailed on one of the “tall ships” in the Ecuadorian Navy, and could relate many a tale, but as I was to find his stories were truth, not “tall tales”. Octavio was an expert on ancient maps and had published “Los mapas del Amazonas y el desarrollo de la cartografía ecuatoriana en el siglo XVIII” (The maps of the Amazon and the development of Ecuadorian cartography in the 18th century). He was also an expert in the early Colonial history of South America and had written, “La expedición a la Canela y el descubrimiento del Amazonas”, (The search for cinnamon and the discovery of the Amazon), which maintained that the lucrative spice trade prompted explorers to enter the unknown lands to the east, ultimately to discover the Amazon River. I had spent years in the Amazonian rainforest, in diamond exploration in Mato Grosso in Brazil, and in Estado Bolivar in Venezuela, so the subject was interesting for me.

Of course we eventually got on the topics of geology and mineral exploration. Octavio maintained that Ecuador was the best country in the world for gold exploration. He said he had lots of documents to back him up. Then he told me a fantastic story….

In 1981, two lads had been out hunting wild pigs when they came across some old tunnels in a hillside, deep in the forest. Scattered around were egg-shaped pieces of granite called “quimbaletes”. I was familiar with these; they are single pieces of shaped stone with a hole drilled through them on which rests a wooden board. The rocks are rounded on the bottom and act as primitive ore crushers. One person throws ore samples under the egg and a second balanced on top of the egg rocks rhythmically back and forth. I had seen these in Peru where small armies of women were rocking literally and figuratively to the music playing in their Sony Walkmans (this is back in the good old days). The Walkmans were new, but the technique dated back well before the Inca. Being indestructible the quimbaletes were historical evidence of past mining activity wherever found.

The two lads had stumbled across the lost gold settlement of Nambija…..and it was rich! Within one month there were 25,000 artisanal miners on the site, consolidated into 75 shaft-sinking operations. By 2000, the site had yielded 2.7 million ounces of gold. But this was only a fraction of what was produced, since the chaotic unregulated settlement yielded perhaps three times this much which vanished into the “Mercado Negro”. Nambija had been mined by the Colonial Spanish, and probably originally by the Inca. It had been abandoned in 1603 after a smallpox epidemic had killed off the native labour. One writer had described Nambija in any case as a “poor mine”, no doubt because it was an underground proposition rather than a surface mine which the Spanish preferred.

I had heard about Nambija. In December, 1997 Terry Bottrill, my former boss at Battle Mountain Gold had asked me if I was willing to replace him on a gold project. He said he was busy with other things and couldn’t finish his contract. I went for the interview and was told to be ready to go to Ecuador just after New Year. At a Xmas party I ran into another ex-employee of Battle Mountain, who said to me, “Did you hear about Terry? He was chased off a property by miners with AK-47’s! Some place called Nambija.” Later I heard stories about company helicopters trying to land having lit dynamite sticks thrown at them by the illegal miners. At the time I was mad as hell, but Terry I’ve forgiven you.

In 1981 there was no national mining law in Ecuador. The Nambija area was invaded by thousands of peasant squatters. Later, both Placer Dome and Newmont Mining would be given mineral rights by the government, but the miners were hostile, and supplied with guns from Colombia they resisted all attempts at removal.

Octavio told me that the Ecuadorian Government was well aware that Nambija had been mined by the Colonial Spanish. In fact, there had been accurate maps showing the precise location of Nambija for more than 200 years! In a disused bedroom against the wall, he dug out a large glass-framed print by Pedro Vincente Maldonado from 1750 (those who are interested can download their own copy from the US Library of Congress website). The script is a bit difficult to read but it clearly locates Nambija.

The Government had surmised that had Nambija come to the attention of their Geological Survey (then part of the Military) before its rediscovery it could have been exploited in a logical and methodical fashion instead of in a chaotic, haphazard, dangerous and environmentally unsound manner. The Government of course was more interested in collecting revenue from a controlled mining operation than anything else! After the rediscovery in 1981 of Nambija, Octavio was employed by the Ecuadorian Government in a curious research exercise: he was tasked to comb the archives for all mentions of historical mines. Together with a small number of other historians the project was begun, but being historians instead of hard-nosed mining people the work dragged on and on. Eventually the Government changed and further research was not supported. The results were hastily thrown into a little paperback book, Investigación Histórica de la Minería en el Ecuador (Investigations into the History of Mining in Ecuador), published by the Dirección de Industrias del Ejército – a part of the armed forces, which provides no maps, no key, and no contextual text, simply excerpts from the documents. The texts are all but impenetrable to the neophyte.

Octavio told me that there were hundreds if not thousands of documents in the archives, many of which concerned the King’s Fifth – the production royalty payable to the Spanish Crown. Mines were scrupulously documented by the Spanish Court. There had been 7 great gold mining districts in the Audiencia de Quito (now Ecuador) in the larger Viceroyalty of Peru (now Ecuador, Peru and Colombia). Ecuador was clearly a great place for exploration!

In 2000, my labours in South Africa exploring for diamonds came to an abrupt end and I decided to return to Ecuador and visit the Galapagos Islands…..something I had always wanted to do since I was a kid. In the company of my friend Peter Werner and his family, we rented a cabin cruiser for a week and toured several islands with a park guide. Octavio, being an expert in the history of the islands asked if he could come along and of course we acquiesced. Pete and I are scuba divers and we got to see some incredible sights, especially huge schools of sharks. This was before the marine park was invaded by illegal fishermen, murdering the sharks for their fins which they sell to China. Octavio had never been snorkelling and Pete’s two sons offered to take him the first day while I grabbed a nap after the previous day’s long flight. After about an hour I woke up when Octavio entered the cabin we were sharing. I said, “Well Octavio, did you see any fish?” Emotionless he said, “Yes, we saw one.” Since he didn’t seem too enthused I guessed he didn’t enjoy the experience. I emerged on deck to shouts from the two boys, “We saw a whale shark! We saw a whale shark!” Of course as a diver this has always been my dream! I turned to Octavio and I said, “I hate you!” We have laughed about this ever since.

On that trip Octavio convinced me to finally take the plunge and do some exploration in Ecuador. Over the next two months I went to Reston, Virginia, to the US Geological Survey Library, and to Ottawa, to the Geological Survey of Canada Library and parked myself in front of every book and report on Ecuador I could find. I resolved to travel to Ecuador just after New Year’s, 2001. I decided to tour the 3 gold provinces of El Oro, Zamora-Chinchipe, and Loja and just see what turned up. In Toronto I picked up Patrick Anderson, who was unemployed like myself, as a confederate. Patrick and I had worked together in Venezuela and Brazil and his Spanish was much better than mine.

We were gone for a month and really didn’t follow any itinerary. We first met with some contacts of Octavio’s and took it from there. There were many dead ends and wild goose chases and we saw a lot of geology. In Zamora, we met with the Regional Director of Mining, Daniel Philco, who spoke fluent English and had done an MSc at Laurentian University in Canada. He arranged for us to go to the mining area of Chinapintza, near the Peruvian border in the far SE corner of the country. This property was mostly abandoned but had been explored by the Canadian company TVX. There was massive evidence of mis-spending on the property: an exploration adit that was way larger than it needed to be, and miles and miles of unsplit and unsampled drill core in the sheds. The gold was coming from a distinctive porphyry with prominent bipyramidal quartz crystals in it.

The following day we went with Philco to an abandoned prospect near the military border base of Paquisha Alto. Daniel explained that this area had yielded 750 grams of gold from a tiny one-man surface washing operation, but he couldn’t understand why gold was coming out of “gray clay”, and “on a hillside” (where there was no river). Immediately while standing on the outcrop I realized that this was a clay-altered quartz porphyry and identical to what we had seen the previous day at Chinapintza about 10 km to the south. It looked really juicy for gold. I decided then and there to file a concession for this area. This was the first of a package which ultimately would become a 93,000 hectare parcel of ground. The “Emperador” concession was granted on April 17th, 2001 and I remember the date because the gold price was almost at rock bottom at $252 USD/oz.

When I got back to Canada and told everyone that I was going to build a new company, working in Ecuador they all said I was nuts! Ecuador had a record of yielding nothing but small mines; good for artisanal miners but that’s about all. I stuck to my guns and told everyone that geology was no respecter of political boundaries, and that there was no reason why Ecuador couldn’t be just as prolific for gold as Peru just across the border.

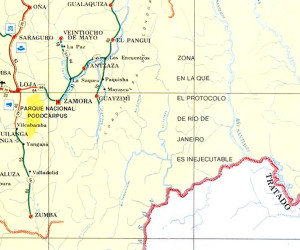

The Emperador area happened to be smack in the middle of an area that was previously the subject of a small border war. Sounds nasty but it was the greatest set-up ever for a mining play. The border between the countries of Peru and Ecuador had been until 1998 the subject of a long running dispute between the two countries. The problem was that when the province of Gran Colombia was broken up after independence from Spain the coastal areas and the Andes were divided between the two countries but the area of the “Oriente” (the East) which was largely unknown and unexplored was only loosely defined. Nobody really cared until the last part of the 19th century when rubber harvesters moved into the Amazon Basin. Suddenly the area had value and both countries claimed each other’s territory. In 1904, the situation was mediated by the King of Spain, but still remained uneasy and during World War II both neighbours tried to exploit the prevailing conditions thinking that foreign powers were too busy to interfere, and invaded each other. The United States was appalled and rather than let the situation spiral out of control set up the Organization of American States to oversee the redrawing of the border. Unfortunately, the work was aided by the US Air Force who took faulty high altitude photographs of the area. When surveyors went on the ground to erect the border monuments they found that a river, which appeared on the Air Force negatives, did in fact not exist on the ground. It was a hair or other artefact on the negs. The results was that for a swath of ground 78 kilometres in length there was no official border, and maps in Ecuador had to show – by law – “Zona en la Que el Protocolo de Rio de Janeiro es Inejecutable” . (more or less “Zone where the Peace Treaty is not in Force”). In this area mining companies were very reluctant to explore in proximity to what they believed might be the border because they might inadvertently be in Peru!

In 1995, the border situation erupted in violence and about 100,000 troops were sent into the area after an alleged incursion into Ecuador by the Peruvian army. Sadly, over a six week period approximately 300 soldiers were killed. The US sent Marines into the area under “Operation Safe Border” and after a mediation chaired by Brazil, Chile, Argentina and the USA the border was mutually agreed as the height of land (the divortium aquarum or Continental Divide between the Atlantic and Pacific). Border monuments were erected in 1998 and the situation is now finally settled for good. When I first went into this area and on subsequent visits I saw small groups vacuum dredging for gold in the river only 4 kilometres or so west of the border. This was highly significant because the source of that gold had to be between where I was observing the miners and the drainage divide….gold couldn’t have leapfrogged from Peru into Ecuador! That meant the bedrock sources had to lie within that 4 kilometre belt along the border. My plan was to grab as much territory along the border as I could get, eventually resulting in a swath 98 km long.

In 1995, the border situation erupted in violence and about 100,000 troops were sent into the area after an alleged incursion into Ecuador by the Peruvian army. Sadly, over a six week period approximately 300 soldiers were killed. The US sent Marines into the area under “Operation Safe Border” and after a mediation chaired by Brazil, Chile, Argentina and the USA the border was mutually agreed as the height of land (the divortium aquarum or Continental Divide between the Atlantic and Pacific). Border monuments were erected in 1998 and the situation is now finally settled for good. When I first went into this area and on subsequent visits I saw small groups vacuum dredging for gold in the river only 4 kilometres or so west of the border. This was highly significant because the source of that gold had to be between where I was observing the miners and the drainage divide….gold couldn’t have leapfrogged from Peru into Ecuador! That meant the bedrock sources had to lie within that 4 kilometre belt along the border. My plan was to grab as much territory along the border as I could get, eventually resulting in a swath 98 km long.

There were other compelling geological reasons too. In the Society of Economic Geology newsletter in October, 2000 (which I received as a member) the border area was discussed as an inverted graben. Not to get too technical, but a graben is an area of profound topographic depression, like the Dead Sea or Death Valley, which is framed by faults which in turn are responsible for the subsidence. In this case the fault basin had been filled in with sediments and then the faults had reversed so that this area was now uplifted by over a kilometre into the air. When you took a GPS reading in the field and superimposed it on a map of the faults you saw that most of the gold occurrences were found on or adjacent to these faults….so the border area was a great place to explore.

Early on in the exploration process we had many run-ins with illegal miners. NGO’s tend to portray illegal miners in a soft diffused light as people making minimal impact on the environment, hand panning for gold in the rivers and streams. Indeed these people existed and we left them alone. The problem was organized teams of men from outside the area who used excavators and other heavy equipment, or explosives and diesel powered Chilean mills. The latter were usually persons with little experience in mining who would go out and buy the largest piece of equipment they could find, while borrowing money from the gold buyers at 5% interest per week. Yes that’s right, per week. In no time at all these people found themselves indentured labour and at the bottom of a debt hole both literally and figuratively. I was sympathetic to these folks however they were squatters, putting tailings into the rivers and freely using mercury to recover gold and they had to go.

On many occasions I was personally threatened; financed by the gold buyers. Sometimes through a loudspeaker mounted on a car, sometimes in press, and often on the radio where I was called a “narco-trafficante” (Drug Lord!) All in a day’s work for most international geologists. They were persistent but they couldn’t run me off. In the village of La Zarza I heard from the local schoolteacher that a community meeting was to be held that weekend and a “vote taken to decide whether or not to let the company stay”. This really had no teeth in law, but practically it was a big deal. I had hired a community relations expert who had advised me in the strongest terms not to go to La Zarza because I would be killed. I went anyway, but I acquiesced to his request that I take security with me. I think I had 5 unarmed uniformed guards and I stayed at a little clapboard inn.

Against advice I took a stroll by myself up the muddy main street Saturday morning and saw a group of people clustered outside the church. I went inside and asked a lady what was going on. She said, “We’re having a Minga.” I said, “What’s a Minga?” She said it was a community event and they were building an addition on the back of the church so the priest had somewhere to stay when he came once a week to deliver mass. I asked, “Can I help?” She said, “Sure you can help.” I went round the back and joined a chain gang of men carrying rocks to lay in the foundations. After about an hour we took a break and I collected the guards who were otherwise unoccupied and we poured and mixed cement, fetched and carried for the rest of the day. At the end of the day I asked the men present, “How many men here have no work?” All the hands shot up. Then I asked, “How many want to work?” Every hand shot up and then one gentleman asked. “What’s the job?” I said, “Clearing trails in the jungle with machetes.” Another said, “We do that all day anyway.” A third said, “What’s the pay?” I said $6 a day, which at the time was more than the national average. Then there were lots of murmurs. I said, “Come to the Casa Comunal Monday morning at 7:30. Bring your identity card and be prepared to work. Only 17 men showed on Monday but they all worked dutifully for the week alongside myself and another geologist. On Friday afternoon they all lined up for their pay, and I gave them cash. I was told later that for some of them it was the only paid labour they had done in their lives. The following Monday I had 50 men show up! Unfortunately I could only take a couple more.

Oh yes, the village vote. Well, I went to the meeting, which was monopolized by a young schoolteacher from outside the area who represented an NGO, who said we would bring drugs and prostitution to the area. Geologist Brent Hendrickson gave a very honest and well thought out address to the crowd about our intentions and the reality of early phase exploration. At one point the teacher said we would produce another “Potosi” bereft of all flora and fauna and an environmental nightmare. Brent pointed out that Potosi had been mined continuously for over 500 years, and that we hadn’t even been around for 5 weeks. The crowd started to laugh and then burst into 50 different conversations. The meeting was adjourned and it seemed that everyone forgot to vote.

That seemed like a close call, but once the locals had worked for us for a period they realized that we didn’t have horns on our heads. One rumour that was dispelled was that we intended to mine and supply “Ecuador’s enemies” with uranium. Each of our geologists carried GPS receivers and in a short time the locals realized these were not “Geiger counters”. After six months of tremendous support and hard work provided by many of the residents we had hired I decided that a big Xmas Fiesta was in order. I borrowed a Santa suit from my brother-in-law and a fake beard, and we bought about 250 dolls and toy trucks. I also bought two cows! We had them slaughtered and dressed and our welder cobbled together a couple of barbeques made out of half oil drums on supports. On the appointed day we had a massive crowd in the village square of La Zarza. Parents had brought their children from five surrounding villages. Each child was placed on my lap for a photo and given a present. I don’t know how my knees held out so long, and I lost about 5 kilos from the heat of the woolen suit! Later we had all the photos developed into glossies and posted on the village notice board for parents to collect. Our workers got a gift basket with a raw chicken, a bag of rice, and some sweets for the children.

That seemed like a close call, but once the locals had worked for us for a period they realized that we didn’t have horns on our heads. One rumour that was dispelled was that we intended to mine and supply “Ecuador’s enemies” with uranium. Each of our geologists carried GPS receivers and in a short time the locals realized these were not “Geiger counters”. After six months of tremendous support and hard work provided by many of the residents we had hired I decided that a big Xmas Fiesta was in order. I borrowed a Santa suit from my brother-in-law and a fake beard, and we bought about 250 dolls and toy trucks. I also bought two cows! We had them slaughtered and dressed and our welder cobbled together a couple of barbeques made out of half oil drums on supports. On the appointed day we had a massive crowd in the village square of La Zarza. Parents had brought their children from five surrounding villages. Each child was placed on my lap for a photo and given a present. I don’t know how my knees held out so long, and I lost about 5 kilos from the heat of the woolen suit! Later we had all the photos developed into glossies and posted on the village notice board for parents to collect. Our workers got a gift basket with a raw chicken, a bag of rice, and some sweets for the children.

Straight Talk On Mining Insights on mining from economic geologist Dr. Keith Barron.

Straight Talk On Mining Insights on mining from economic geologist Dr. Keith Barron.

I love how you care about the people as well as the rich resources of their land. You’ve got quite the heart.

What a great read.

I knew Keith was a winner when I saw a parrot on his arm and a warm smile his face….

I definitely want to buy his book…..How ?

thanks

It’s a Labour of Love and a Work in Progress! I hope I can have it on Kindle sometime in the next 6 months. It depends on my (ever increasing) workload!

I was so happy to read about your sucesses!

You truly are a fine man with heart worth more than all the gold you have discovered.

This is very kind of you Donna. All the best!

I suspect you are missing a pocket button on your green shirt. I wear a designated shirt when I have my Macaw on my arm. The shirt is missing ALL of it’s buttons!

Keith, Excellent first chapter. Well done! Cannot wait to read the rest.A long way from smuggling over weight loads of garnets out of Dillon.A perfect storm of events finds me He also is an expert broke and stranded in Safford Arizona at present I am taking a break from therapy and in good spirits. “I feel happy”.By luck or fate, have happened across an interesting fellow who has spent the bulk of his life collecting fossils, crystals and minerals professionaly He discovered six new species of shark along with other rare fossils and gems.He likes to reopen old mine sites, blasting and hand digging for goodies.He also is a rock surgeon, reconstructing crystal/mineral structures.If you have the book American Mineral Treasures, G. Staebler/W. Wilson, he worked on many of these specimens, including “The Dragon”.An 18 cm. exquisite gold structure, which was in 3 pieces when he started on it.Found in the Crystal Mine in CA 1998, it now is in the Houston Museum of Natural History.William Hawes is closing in on 70 years young and could out hike me in my best of days still- a true character.I am house sitting for him while he at a show.His considerable Geologic/ Earth Science library keeps my mind occupied.It is refreshing to recconect with earthly treasures again.Hope this finds you well. Take care mate. John List. email: johnlistpt@gmail.com

Keith, Apologize for the initial comment. I thought this was going into your personal email. Im looking forward to the rest of your book. thank you for all your insights into connecting with earthly treasures.

John List.